This article is a report on health care provided to youth with gender dysphoria at a clinic in British Colombia, Canada. I’m going to focus on just the demographics in this post and do another post later.

QUICK OVERVIEW

The clinic saw a dramatic increase in the number of their teenage patients from 2006-2011. This is similar to other clinics serving teenagers with gender dysphoria.

Most of their patients were trans men (born female). This is similar to the current situation at other clinics for teenagers, but different from the past at other clinics. It is also different from most European clinics for adults.

Their patients had other psychiatric diagnoses including mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and eating disorders. The patients in this study had more psychiatric problems than teenagers studied at a clinic in the Netherlands.

7% of their patients had an autism spectrum disorder. This is similar to the results of a Dutch study of children and teens with gender dsyphoria.

Suicide attempts are a serious problem among their patients. 12% of their patients had attempted suicide before coming to the clinic; 5% attempted suicide after their first visit to the clinic. The decrease is encouraging, but clearly we need to do more to help patients during and after transition.

Some of their patients had to be hospitalized for psychiatric problems. 12% of their patients had been hospitalized before coming to the clinic, but only 1% were hospitalized after the first visit. Again, we need to be sure to provide support during and after transition.

THE INCREASE IN TEENAGE PATIENTS

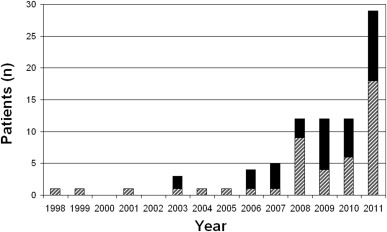

The clinic has seen a fairly dramatic increase in the number of teenage patients from 2006-2011. They went from fewer than 5 cases/year before 2006 to nearly 30 cases in 2011.

Number of new patients with gender dysphoria seen in 1998-2011. MtF, black bars; FtM, hatched rectangles.

This parallels what has happened at a similar clinic in Toronto, Canada and a clinic in the Netherlands.

Unlike the other two studies, the majority of the patients at this clinic were always trans men (born female). In fact, before 2006 almost all of the patients were trans men. After 2006, the number of trans women patients (born male) began to increase. However, trans men still made up 54% of all the patients they saw between January 1998-December 2011.

This is different from the pattern found in the clinics in Toronto and Amsterdam. In those two clinics the patients were mostly trans women before 2006, but after 2006 they were mostly trans men.

It’s hard to know what these numbers mean because we don’t know how common gender dysphoria is among teenagers.

“The prevalence of adolescent-onset gender dysphoria is not known, and there are limited accurate assessments of prevalence of transgenderism in adults in North America. However, the prevalence of adults seeking hormonal or surgical treatment for gender dysphoria is reported to be 1:11 900 to 1:30 400 in the Netherlands.”

Does this increase reflect an increase in the number of teenagers with gender dysphoria? If so, why are the numbers increasing?

Alternatively, is this increase due to people with gender dsyphoria seeking physical transition at a younger age?

Statistics on most European clinics have shown many more trans women transitioning than trans men (the pattern is reversed in Japan and Poland). Now the statistics on Canadian and Dutch teenagers show more trans men transitioning than trans women.

Are there more trans men than in the past? If so, why?

Or are trans men transitioning at a younger age than trans women? But then why did the other two clinics treat more teenage trans women than teenage trans men in the past?

BASIC DEMOGRAPHICS OF THE PATIENTS IN THIS STUDY

The clinic at British Colombia Children’s Hospital saw 84 youth with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria from January, 1998 to December, 2011.

45 of the patients were trans men, 37 were trans women, and 2 were males who weren’t sure of their gender identity.

Two of the trans women had disorders of sex development – one had Klinefelter syndrome (XXY chromosomes) and one had mild partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (i.e. her body made androgens, but they didn’t fully affect her).

The median age at the first visit was 16.8, the range in ages was from 11.4 to 22.5.

At the first clinic visit, most patients were in school grades 8-10 (32%) or grades 11-12 (48%); 12% were in grades 5-7, and the remaining 8% were in college/university or no longer attending school.*

PSYCHIATRIC COMORBIDITIES

Diagnoses made by a mental health professional:**

35% of the patients had a mood disorder (20 trans men, 7 trans women and probably the two males with uncertain gender identity)

24% had an anxiety disorder (15 trans men, 4 trans women and probably one male with an uncertain gender identity)

10% had ADHD (2 trans men, 6 trans women)

7% had an autism spectrum disorder (2 trans men, 4 trans women)

5% had an eating disorder (2 trans men, 2 trans women)

7% of their patients had a substance abuse problem (2 trans men, 4 trans women)

26% of their patients had two or more mental health diagnoses (12 trans men, 9 trans women) and probably one male with an uncertain gender identity.

Suicide attempts:

10 of the teenagers attempted suicide before coming to the clinic (12%). 6 of them were trans men and 2 were trans women. Perhaps the other two were the two males who weren’t sure of their gender identity.

4 of the patients attempted suicide after the first visit to the clinic (5%). Three of them were trans men and one was a trans woman.

Psychiatric hospitalizations:

12% of the patients had been hospitalized for a psychiatric condition before coming to the clinic – seven trans men and three trans women.

One trans man was hospitalized for a psychiatric condition after the first visit to the clinic (1%).

Conditions requiring hospitalization included posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, substance abuse, behavioral issues, psychosis, and anxiety.

Mood, puberty blockers, and hormones:

One trans woman and one trans man discontinued the use of a puberty blocker after they developed emotional lability (7% of the patients who took the puberty blocker). The trans man also had mood swings.***

One trans man had significant mood swings as a side effect of testosterone treatment. (3% of the patients who took testosterone.)

Two trans men temporarily stopped testosterone treatment due to psychiatric conditions – one was depressed and one had an eating disorder. (5% of the patients who took testosterone.)

One trans man temporarily stopped testosterone treatment due to distress over hair loss. (3% of the patients who took testosterone.)

Gender differences:

Trans men were significantly more likely to have depression or anxiety disorders than trans women. 44% of trans men had mood disorders compared to 19% of trans women. 33% of trans men had anxiety disorders compared to 11% of trans women.

There were no significant gender differences in other mental health issues.

27% of trans men had two or more psychiatric diagnoses compared to 24% of trans women. This seems surprising given that trans men were more likely to have mood and anxiety disorders.

The most important issue is the number of suicide attempts.

Why were there four suicide attempts after the first visit to the clinic?

Were the suicide attempts related to the two patients who developed emotional lability on blockers? or the trans man who developed mood swings after taking testosterone?

Were they related to the trans man who stopped taking hormones due to depression? Was he the same person as the trans man who developed mood swings on testosterone?

What about the trans man who stopped his hormones due to an eating disorder?

When were the suicide attempts? Were they before the patients got blockers or hormones? Did they happen after stopping hormones for any reason? Or were the patients already on hormones or blockers?

Could they have been prevented by more therapeutic support before treatment? during treatment?

Is there a way to identify which patients are at risk for suicide attempts during or after treatment?

It is encouraging to see that there were fewer suicide attempts after the first visit to the clinic than before, but it is not enough. We need to do more.

We also need more data on the decrease in the number of suicide attempts after coming to the clinic. Was it statistically significant? Was the time period before the first visit to the clinic equal to the time period after the first visit to the clinic?

Psychiatric comorbidities comparison

Compared to a clinic in the Netherlands, these patients were more likely to have mood disorders (35% vs. 12%), but about as likely to have anxiety disorders (24% vs 21%).

5% of the Vancouver patients had an eating disorder while none of the patients in the Dutch study did.

7% of the patients in this study had a substance abuse problem while only 1% of the patients in the Dutch study did.

26% of the patients in this study had two or more psychiatric diagnoses. In comparison, only 15% of the teenagers in the Dutch study had two or more psychiatric disorders.

Finally, the Dutch study found that trans women were at higher risk for having a mood disorder or social phobia while this study found that trans men were at higher risk for mood and anxiety disorders.

Why is the psychiatric comorbidity higher in the Vancouver patients?

The authors of the report suggest that it might be because the average age of their group was higher than the average age in the Dutch study – 16.6 year vs 14.6 years. It might simply be that older teenagers have had more time to develop mental health issues.

They also suggest that there could be differences in diagnostic criteria. Both groups seem to have been using DSM-IV diagnoses, but the Vancouver data was based on clinic notes while the Dutch data was based on interviewing parents. It may be that parents underestimate their children’s problems. For example, they might not realize that their teenager has a substance abuse problem or an eating disorder.

In addition, the Vancouver study includes all 84 patients their clinic saw between 1998-2011. In contrast the Dutch group invited 166 parents to participate in their study, but only 105 parents did so. It is possible that the 61 parents who did not participate had children with more problems, although the authors suggest that the inconvenience of travelling to the center was the main issue.

Finally, the Dutch group has 17 teenagers who were referred to the clinic but dropped out after just one session, “mostly because it had become evident that gender dysphoria was not the main problem.” These patients might have had more psychological comorbidity than others.

It is hard to compare this to the Vancouver clinic, however, because the Vancouver clinic’s focus is on endocrine care. 93% of the patients they saw had already been diagnosed with gender dysphoria by a mental health professional. Were there teenagers in Canada who discovered that gender dysphoria was not the main problem and did not go on to the clinic? If so we would expect the two clinics to have similar rates or psychological comorbidity. If not, we might expect a higher rate of comorbidity in Canada.

A final possibility is that the Canadian teenagers with gender dysphoria simply have more psychological problems than Dutch teenagers with gender dysphoria. Perhaps they experience more bullying and violence. Perhaps they had less supportive parents.

As usual, we need more studies. Why are the numbers of teenagers at clinics for gender dysphoria increasing? What is the prevalence of gender dysphoria among teenagers? How common are psychological comorbidities? Are trans men or trans women more at risk for depression and anxiety? What can we do to prevent suicide attempts after treatment begins? How can we better support patients with gender dysphoria during and after transition?

Original Source:

*This would suggest that 48% of the students were 16-17 years old, 32% were 13-15, 12% were 11-12, and 8% were 18-22.5.

** The table indicates that these were diagnoses made by a psychiatrist or psychologist. There were other diagnoses the authors didn’t include in the table: 1 patient with trichotillomania, 2 with borderline personality disorder, 1 with psychosis not otherwise specified, 1 with adjustment disorder, 2 with tic disorders, and 1 with oppositional-defiant disorder. I am not sure why these diagnoses weren’t included; perhaps they weren’t made by mental health professionals.

***The blockers being used were gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog or GnRHa.